Tissue Types

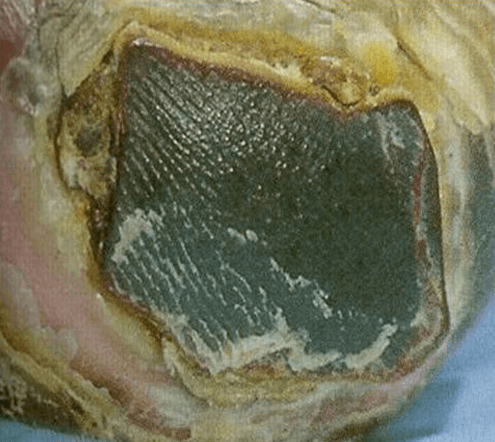

Black (necrotic tissue)

Black necrotic tissue, or eschar, is devitalised dead tissue. It often appears black, but may also appear brown or grey when hydrated. Necrotic tissue can initially be soft, however, the dead tissue can lose moisture rapidly, and become dehydrated with the surface becoming hard and dry.

NB: Necrotic tissue on the feet and leg lower limb (including feet) should be treated with great caution. The wound should be covered with a dry dressing, and a vascular status established before treatment is carried out. Referral to the relevant speciality, e.g. vascular or diabetic foot clinic as per local policy. Delaying referral could threaten the limb (Eagle, 2009).

Management of necrosis should include identifying the underlying cause of the necrosis (e.g. pyoderma gangrenosum, peripheral arterial disease, calciphylaxis, insect/snake bite) and implementing the appropriate treatment before the dead tissue can be dealt with. This can encompass administering antibiotics, anti-venom and or alleviating pressure on the wound area to restore perfusion (Carpenter, 2017; Wound Source, 2019).

Once the cause has been established, the necrotic tissue, where appropriate, will need to be removed so that wound healing can begin. Unless removed, the eschar will delay healing as healing cannot proceed effectively without a moist wound environment. The necrotic tissue is derived from granulation tissue after the death of fibroblasts and endothelial cells (Collier, 2004).

Caution should be applied with wounds showing signs of pyoderma gangrenosum and calciphylaxis. A referral to a specialist health care professional for further advice may be required (Carpenter, 2017).

Necrotic tissue also acts as a culture, providing an ideal breeding ground for bacteria (Eagle, 2009). Removing this tissue will also allow for accurate assessment of the wound bed, as the necrotic eschar can mask the true size of the wound.

The presence of necrotic tissue presents a challenge for health care practitioners. The removal of necrotic devitalised tissue can be achieved by a variety of evidenced-based interventions (see module 4). Removal can be achieved with dressings that rehydrate the hard tissue. Larvae can be used if the necrotic tissue is soft. Within the nursing profession, conservative sharp debridement, defined as the removal of dead tissue with a scalpel above the level of viable tissue, has been identified as a high-risk clinical procedure.

Yellow (sloughy tissue)

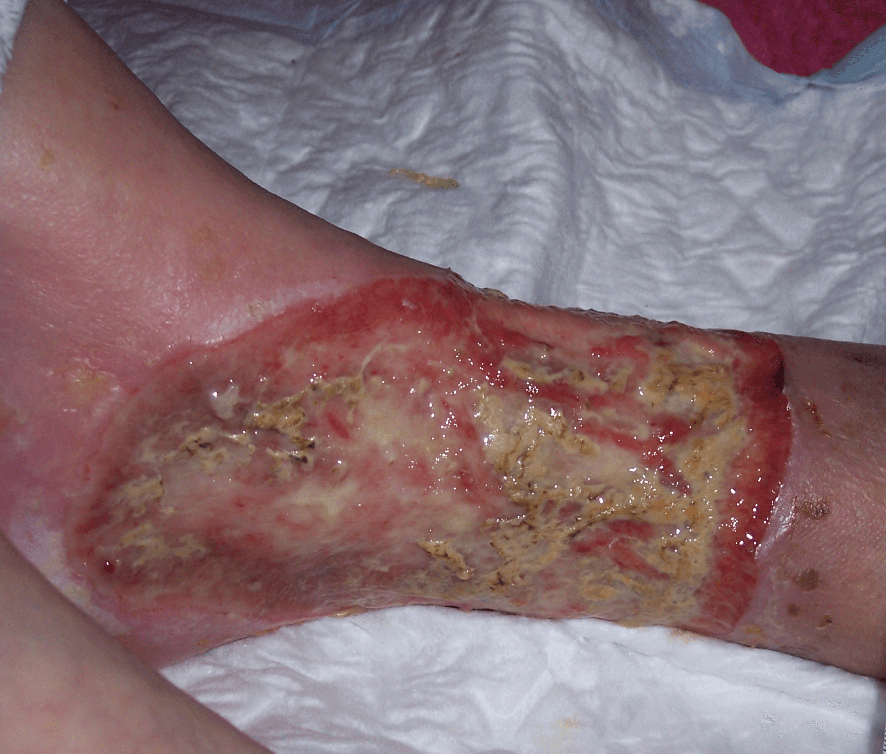

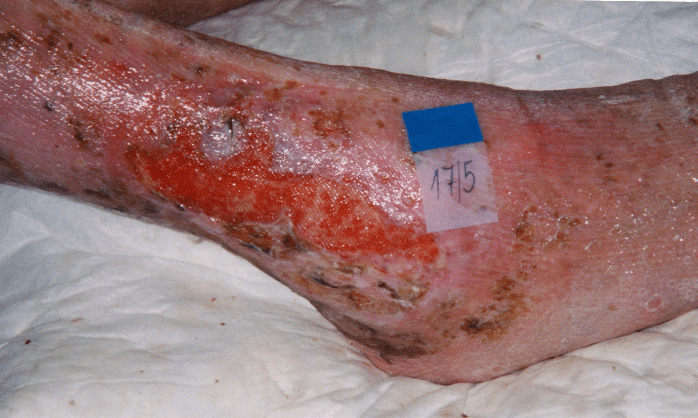

Sloughy tissue is fibrous and yellow, adheres to the wound bed and cannot be removed on irrigation. It is also a type of necrotic tissue. Slough consists of dead cells and wound debris which should be removed to enable healing to take place. This is often referred to as de-sloughing.

Slough may predispose to wound infection and delay healing; however, the presence of slough is not necessarily indicative of clinical infection. Exposed tendons should not be mistaken for slough.

Slough can be found as patches across the wound bed. Removal of the slough is done so by the application of a suitable dressing, which enables the wound to progress to healing (Eagle, 2009).

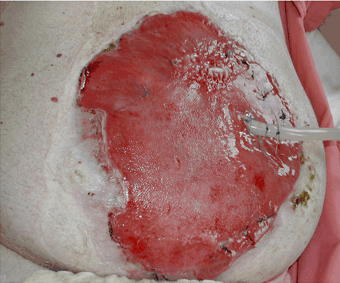

Red (Granulation Tissue)

Granulation tissue fills the wound as it is healing. The tops of the capillary loops make the wound appear red and granular. It is firm to the touch, painless, and does not bleed easily. Bright red granulation tissue, which bleeds easily, may indicate infection.

The aim of wound management for a granulating wound is to:

- Manage excess wound exudate

- Protect from infection

- Maintain a moist wound environment for wound healing

- Encourage growth of new tissue

(Eagle, 2009)

PINK (EPITHELIAL TISSUE)

Epithelial tissue is formed in the final stages of healing. This tissue forms the new epidermis. Epithelial tissue is superficial, pinky white tissue that migrates across the wound from the wound margin, hair follicles, or sweat glands. It will cover the granulating tissue and is the final visual sign of healing.

In shallow wounds with a large surface area, islets of epithelialisation may be seen.

Infected Tissue

An infected wound can result in a delay in the wound healing process by wound size increase, the shape of the wound changing, and general breakdown. Infection results in increased inflammation, delayed collagen synthesis, prevention of epithelialisation, and increases the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, which may lead to additional tissue destruction.

Wound infection and associated delayed healing present considerable challenges for clinicians, particularly with respect to identifying clinical infection and choosing appropriate treatment options (EWMA, 2005). Clinical signs of infection include erythema, swelling, local warmth/heat and pain (EWMA, 2005). (For further information on tissue types, see Module 4).

Criteria for identifying wound infection:

- Abscess

- Cellulitis

- Discharge (serous exudate with inflammation, seropurulent, haemopurulent, pus)

Suggested additional criteria:

- Delayed healing (compared with normal rate for site/condition)

- Discolouration of friable granulation tissue that bleeds easily

- Unexpected pain/tenderness

- Pocketing at base of wound

- Bridging of the epithelium or soft tissue

- Abnormal smell

- Wound breakdown

(Cutting & Harding, 1994; Dowsett, 2011)

The normal microbial state of a healing wound is that of colonisation, which represents a stable state where growth and death of organisms are balanced or below the immune system's healing disruption threshold (Heinzelmann et al., 2002).